REDCAT’s annual NOW Festival is a laboratory for new, urgent artistic creations during every summer, for 14 years now. The second week in the series continued in this vein presenting, Tales Between Our Legs, Vivian Bang and Nickels Sunshine. Each of work brought unexpected humor, poignant, forgotten Los Angeles history and homage to choreographic styles of dance.

Tales Between our Legs (TBOL) performed, A Dismal Glimpse at a Script We Create to Keep Us Moving Forward. Three collaborators, Megan Fowler-Hurst, Mackenzey Franklin and Sarri Sanchez make up TBOL. The long title surmises this multi-media creation. One thing, purposefully, had little to do with the next. Yet it engaged, exactly because it was not “dismal” but rather, satirical.

Following a brief opening video shot in extreme close up’s of a human eye and a multiple ringed hand, a woman entered stage within a red birdcage. Bird calls went on for a short time as the woman looked toward the sounds, listening. Soon after, two performers in fox heads entered holding a yellow balloon. One after the other, each one moved with the balloons motions with their breaths.

Soon after, bird-cage lady exited with the sound of a door shutting after her. Cheers from a television sitcom laugh track followed. Sequences followed in this ‘non-sequitur’ manner. The bird-cage lady returned and suddenly the room became immersed in some great, funky, techno music. The woman in the cage danced, strobe lights flashed and the two Fox’s images appeared on the video screen within clouds.

The ending was another highlight. The three performers returned wearing everyday clothes and sat down in red chairs. A taped post-performance dialogue began on the piece that we just saw.

The performers sat, visibly flummoxed, close to falling off their chairs, while a recording played in the voices of a critic and an artist’s silent reactions in her head. The critic’s voice employed progressively elaborate hyphenated phrases within the current social fabric. The artist voice responded, dryly rebutting the comments made, such as, “cis white feminism is not inclusive,” and “I don’t need your mansplaining.”

The conversation quickened, filled with longer growing phrases and adjectives at near breakneck pace. In a clever and humorous turn, the dialogue highlighted the contrast of what people say and what they mean.

Can You Hear Me / LA 92

In Can You Hear Me / LA 92, writer and performer, Vivian Bang poignantly re-visits a forgotten history of the Los Angeles 1992 uprising. Recalled through the perspective of Korean – Americans, this was a visually and viscerally striking piece. Bang came out in a white, loose jumpsuit with a stark white banged bob.

She narrated as a Korean immigrant woman who came to the United States with her husband and two boys. She believed, “the U.S. is a place where dreams come true.”

Telling the story of her and her husband’s long days working at the shop they owned, Bang’s character conveyed the regret she felt that they never had time to see their kids.

“I tell them what to eat for dinner over the phone,” she said. “I missed my kids growing up, I cry.”

Bang narrated to a backdrop of video including herself in the same costume walking around Koreatown markets.

She continued, leading up to the night of the Rodney King verdict. She described how their store burned down and they called the police. No one came. Her husband was shot. She realized, “the police don’t care about us,” she said. “No one cares who shot him.”

“It’s our fault (we lost the store) because we had no insurance.”

Bang paused and outstretched a cloth panel from her jumpsuit employing a screen. She slowly crossed the stage as a projected photograph of a Korean woman kneeling at a grave appeared.

When she began speaking again she narrated the untold stories and events. It was as though she announced a news cast we had never heard of what was really going on in Los Angeles during that time. Over 2,000 Korean businesses were destroyed. There was an economic recession. At the same time, there was an influx of Korean’s also doing business where no one else would.

“The media always published stories of black crimes on Korean stores, even if race had nothing to do with the crime, without mentioning economic disparities,” Bang said.

On Radio Korea you could hear live calls when the riots happened. It became a command post serving as a lifeline for Koreans. The police arrested armed Korean volunteers instead of coming to help. And the National Guard headed toward the suburbs instead of the place of most danger in Koreatown.

In closing, Bang implored that we need our communities and to know our neighbors. What has an effect on them has an effect on you. These uncommonly heard narratives of people of L.A. illuminate our neighbor’s struggles and triumphs. They show us how connected we are.

Take Me With You

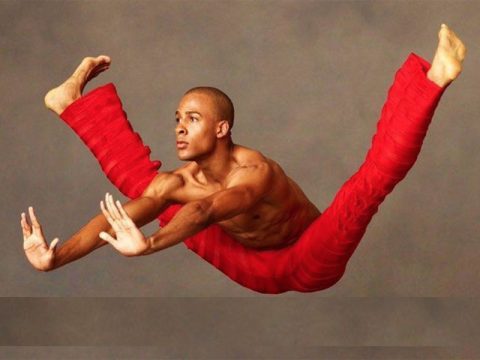

In a nod towards choreographic styles of modern dance pioneers, Vaslav Nijinsky and Martha Graham, Nickels and Sunshine’s, Take Me With You examines forming connections and then having them dissolve.

The work had no props other than one green coat on the floor and hanging rolls of paint splotched paper on each side of the stage. Costumed in non–gender conforming roles, bodies came together through dance movements. They separated again only to reconfigure with different numbers of people. The one consistent motion at various intervals was each of the dancers ran toward a wall on one side of the stage. They practically threw themselves at it, whaling in grief, and then ran away from it, looking back, still screaming. It was strange because there was no solution to this repetitive pattern. But even without culmination, the dancers’ movements were easy to get lost in. With much running, leaps and cylindrical circles carried out, this energetic piece, even within the feeling of turmoil, offered a certain peace.